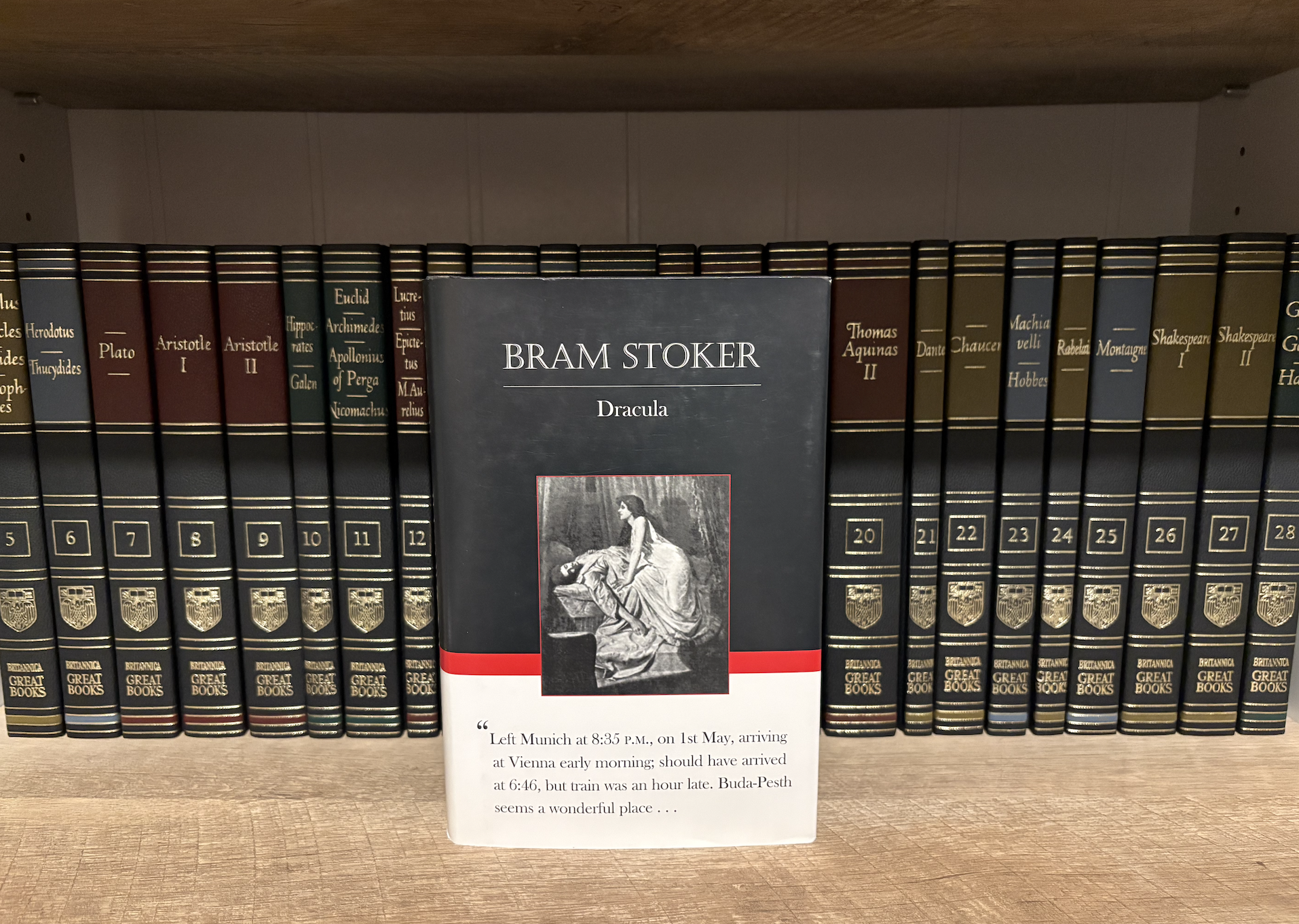

Dracula by Bram Stoker – A Battle of Light and Darkness, Faith and Reason

Bram Stoker’s Dracula is often remembered for its gothic atmosphere, mysterious count, and the creeping sense of dread that stalks every page. While many modern discussions dwell on its sensual undertones, the novel is just as much a timeless meditation on two deeper struggles: the eternal clash of good and evil, and the uneasy tension between science and superstition.

From its opening pages, Dracula sets the stage for a moral battle. The Count himself is more than a man, he is a personification of evil, ancient and cunning, thriving on the lifeblood of the innocent. Opposing him is a diverse band of protagonists: Jonathan Harker, Mina Murray, Lucy Westenra, Dr. Seward, Lord Godalming, Quincey Morris, and the incomparable Professor Van Helsing, each bringing their own strengths, convictions, and weaknesses to the fight. They are flawed but united in a cause greater than themselves, bound together by courage, loyalty, and love.

Here, good and evil are not murky or ambiguous. Evil is real, active, and deliberate. It preys on the vulnerable, isolates its victims, and hides in darkness. Good, by contrast, demands sacrifice; both personal and collective. The heroes must give of their time, their safety, and ultimately their lives in some cases to bring evil into the light and destroy it. In this sense, Dracula reads like an allegory for the Christian spiritual life, where virtue demands vigilance, unity, and self-denial in the face of relentless opposition.

Equally compelling is Stoker’s exploration of science and superstition. The late 19th century was a time of rapid scientific advancement, and Dracula captures that excitement and the skepticism it often brought toward old-world beliefs. Dr. Seward, for example, embodies the modern scientific mindset: meticulous, rational, and unwilling to accept anything that cannot be explained by natural causes. Yet as events unfold, even the most rational minds are forced to confront the reality of forces beyond empirical proof.

This tension comes to a head in Van Helsing, a man who refuses to discard either faith or reason. He is a physician and a scholar, yet he also wields garlic, crucifixes, and the lore of centuries past. In Van Helsing, Stoker presents a bridge between two worlds: the empirical and the mystical, the measurable and the miraculous. His character suggests that the truest wisdom comes not from rejecting superstition outright, but from discerning what ancient truths remain valid, even when they defy contemporary scientific frameworks.

By the novel’s end, the resolution of both conflicts, good’s triumph over evil, and the integration of faith with reason, feels earned. The group’s success depends not on science alone, nor on blind faith, but on a synthesis of the two. In this way, Dracula is not only a thrilling gothic horror but also a reminder that the most enduring victories come when we draw on all available tools: the sharpness of our minds, the steadfastness of our moral convictions, and the wisdom of traditions that predate us.

For readers today, Dracula offers more than chills—it offers a blueprint for how to confront the darkness in our own lives. Evil still seeks the shadows, and truth still requires the courage to bring it into the light.

For more talk about the classics and other books I’m reading, head over to the Book Corner.

Find Dracula on Amazon.